By Pamela A. Lewis

Even those who rarely, if ever, set foot into a museum or art gallery, probably know who Andy Warhol was. His pallid, high cheek-boned face, topped by a thatch of white hair, and his deep-set penetrating eyes have been as recognizable to the don’t-know-nothin’-’bout-art set as they were to the sophisticated aficionados who flocked to the artist’s exhibitions and avant-garde films. Warhol’s soup cans, dollar signs and celebrity portraits not only defined his body of work, but became the attributes of one of the twentieth century’s Pop art saints.

Of course, Warhol was no saint. His life — and by extension, his art — reflected the restlessness of the 1960s, where challenges to socio-politico structures and conventional sexuality roiled American culture. Warhol’s full engagement with these movements engendered a persona that was part social critic, part filmmaker, and part promoter of emerging artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat.

However, the Brooklyn Museum’s “Andy Warhol: Revelation, exhibition, open through June 19, explores the artist’s little-known but also lifelong engagement with religious belief and to what extent his Catholic faith informed his art, while the institutional church was also subjected to his criticism.

As art historian John Richardson, who eulogized Warhol at his memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 1987, observed, his spiritual side may have come as a surprise to many, but it did exist and was key to understanding the artist’s psyche.

Organized by José Carlos Diaz, chief curator of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, and overseen by the Brooklyn’s Associate Curator for Feminist Art Carmen Hermo, the show, as its title suggests, reveals an artist for whom religious belief was at once a source of inspiration and of anxiety.

Born Andrew Warhola in 1928 in Pittsburgh to parents who emigrated from what is now Slovakia, Warhol grew up in the city’s Ruska Dolina neighborhood and attended St. John Chrysostom, the Byzantine Catholic church that was the center of the Carpatho-Rusyn working-class community where Warhol spent his childhood and early youth.

It was at St. John’s, which he attended every weekend with his mother Julia, that the young Warhol absorbed the church’s rituals and saw the richly painted icons of Christ and of the saints that lined its walls.

St. John’s elaborate and powerful iconography would remain Warhol’s frame of reference for much of his future artwork, and within the show’s seven sections it is the religious and cultural point of departure for Warhol’s journey of faith and art.

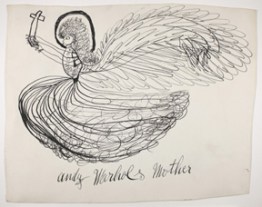

In the section called “Immigrant Roots and Religion,� religious ephemera from his early life — prayer books, crucifixes, his certificate of baptism, and brightly-colored pysansky Easter eggs — are on display in the cases that introduce the exhibition. (Even Julia’s whimsical doodles of angels and cats share wall space with her son’s early artistic forays.)

These personal and, in some cases devotional, items are the context that informed Warhol’s religiously-referential works, such as an exquisite gold-leaf collage of a Nativity scene, in all likelihood influenced by the gold-ground icons he would have seen in St. John’s, and which would culminate in the series of paintings The Last Supper.

Warhol’s personal religious fervency is still a subject of debate, considering his more familiar sex-drugs-and-rock-and-roll image. But his representations of religious figures and symbols were purposely irreverent.

A series of paintings from the section “Guns, Knives, and Crosses� (1981-82), which Warhol did for an exhibition in Madrid of the same title, presents the troubling connection between redemption and violence.

3—— Canvases depicting screen-print crosses reference what he called “the Catholic thing,� given the religion’s dominance in Spain from 1492 through Generalissimo Franco’s fascist dictatorship (1936-75), while the guns and knives recall the Spanish Civil War.

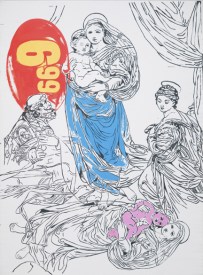

The use of bright colors and of repetition downplays the religious symbol’s universality. Warhol’s “Raphael Madonna-$6.99� (1985) is an acrylic and silkscreen ink re-interpretation of Raphael’s Renaissance masterpiece, “The Sistine Madonna.�

Warhol puts aside his affection for religious iconography by appropriating this beloved composition to take aim at American consumer culture, where even religion is commoditized, as suggested by the work’s looming $6.99 price tag in the background.

He makes this point again in the painting “Christ, $9.98�, based on a newspaper ad for a night light shaped like Jesus.

In the 1980s, Warhol collaborated with Jean-Michel Basquiat — who was also raised Catholic — to create “Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper).� The work comprises white punching bags, each bearing Warhol’s hand-painted face of Christ, lifted from “The Last Supper,� on each of which Basquiat wrote the word “JUDGE.�

“The Catholic Body,� which focuses on the tension between Warhol’s Catholic upbringing and his identity as an out gay man, is the show’s strongest section. Here, works such as “The Last Supper (Be a Somebody with a Body),� where a blowup image of a beefy bodybuilder is superimposed over Warhol’s hand-painted face of da Vinci’s Christ from “The Last Supper,� intertwine carnality and sanctity.

They point as well to the artist’s fascination with the body, yet to his conflicted feelings regarding his own in the context of commercial images of conventional physical attractiveness and strength (which he obsessively tried to attain).

Whether to be understood as a reference to Christ’s being scorned and judged before his crucifixion, an allusion to the artists’ critical hits from the press and wider art market, or the Catholic church’s vilification of their nonconforming sexuality, “Punching Bags� pulls no punches.

They also explore his fears of vulnerability and disease, in the face of the then-worsening AIDS crisis and the Catholic church’s condemnation of homosexuality.

His fears of victimization were realized when, in 1968, radical feminist Valerie Solanas shot and severely wounded him.

With a nod again to Catholic iconography, Richard Avedon’s now-famous 1969 photo shows Warhol displaying his surgery-scarred bare torso and posing in the manner of Saint Sebastian, who was martyred by being shot with arrows, as he is depicted in countless paintings in Western art. The artist also extends his hands in a resurrected-Christ pose, suggestive of having been restored to new life through the miracle of medicine.

In his well-known “Jackie� series (1964), which presents four somber blue and black acrylic and screenprint images of the widowed First Lady attending her husband John F. Kennedy’s funeral, Warhol highlights his — and society’s — complex attitude toward women (especially celebrities).

Taking stylistic cues from Eastern Catholic icons, Warhol elevated the elegant, Catholic, and culturally astute young woman to a secular saint, whose face of eternal sorrow would inspire quasi-national veneration.

Since childhood, Warhol was familiar with Leonardo’s 15th century fresco “The Last Supper,� and he did several versions of the work prior to the last series from 1986 displayed in this show.

In “Marilyn Monroe: Marilyn,� (1978) Warhol passes judgment on American culture’s treatment of this movie star’s and all female celebrities’ bodies. Using a palette ranging from dark to vivid to manipulate and abstract Monroe’s recognizable features, he draws attention to the darker realities of America’s worship of fame and wealth and to the erotic objectification of the female body.

The pink-hued “Last Supper,� despite expressing the kitsch usually associated with his work, demonstrates Warhol’s deep reverence for da Vinci’s mural, and also evinces a subtle plea for grace and healing of the suffering which the gay community was experiencing during that time.

Warhol once instructed an interviewer to look at the surface of his paintings and films and himself to find the real Warhol, because there was nothing behind that surface.

While his art is for some an acquired taste, its explorations of cultural ambiguity, of the role and representation of women, and of his appropriations of Renaissance masterpieces, “Revelation� takes us behind the surface and acquaints us with Warhol’s creative process.

Uppermost in this show is the acknowledgement that faith occupied a more central place in this artist’s life and work than we knew.

Based in New York, Pamela A. Lewis writes about topics of faith.